BusinessInsider– Ads.txt has been billed a high profile, potentially high impact effort to clean up digital advertising. But it’s been moving in slow motion.

Large brands, publishers, ad agencies, ad tech middlemen, industry trade groups and even Google have rallied behind the initiative.

Indeed, the promise of ads.txt is to make it clear which third parties are authorized to sell publishers’ ad space, and which aren’t. Ideally, if widely adopted, ads.text should prevent big web publishers like say the New York Times from getting ripped off by scam artists falsely claiming to represent their ad inventory.

But over six months in, uptake of the industry-backed effort has been noticeably sluggish among publishers.

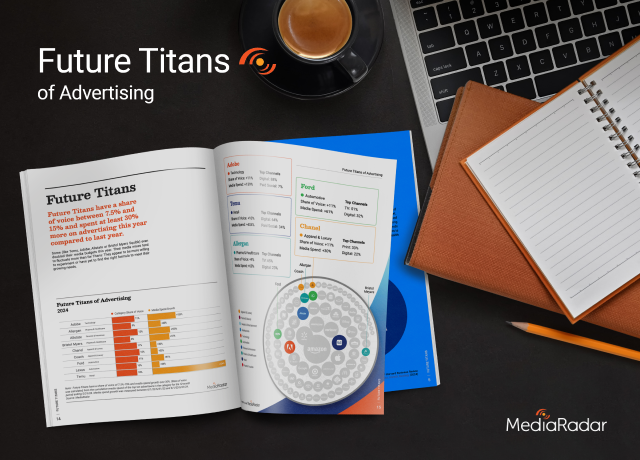

According to a study by ad intelligence platform MediaRadar on ads.txt, publisher adoption of the tactic— where they essentially list their authorized inventory on their web servers — has lagged.

MediaRadar used its proprietary ad-tracking intelligence software to audit 3,000 publisher sites, and found that only 20% of these publishers had adopted it. This is a smaller number than the number put out by Google in November, according to which 750 of the top 2,000 comScore publishers have ads.txt files. Google declined to comment.

“We have seen relatively modest adoption,” said Todd Krizelman, CEO of MediaRadar. “The largest sites are moving quickly, but only 20% of all publisher sites we track today have taken advantage of ads.text. It’s a reminder of the power of inertia, and the importance to really evangelize the benefits of this new way to stop spend on unauthorized counterfeit ad inventory.”

Launched by the Interactive Advertising Bureau Tech Lab in May, ads.txt is an effort aimed at wiping out fraud that’s dubbed ‘spoofing’ by the industry, where unauthorized sellers trick ad buyers into paying for space they are not actually getting. You think you’re buying ads on CNN.com, but you’re really buying ads on a no-name website, for instance.

To combat unauthorized sellers from peddling counterfeit inventory, web publishers simply put a text file on their web servers that lists their authorized inventory sellers.

Prominent publishers that have adopted ads.txt include The New York Times, The Washington Post, ESPN, Forbes, Bloomberg and The Wall Street Journal, among others (Business Insider uses ads.txt too). But a quick scan of some domains by Business Insider revealed that some recognizable publishers, including Oath properties like AOL.com, MSN.com, Yahoo.com as well as Slate don’t seem to have implemented it.

“We’ve been doing our due diligence on the back end and are actively working to implement ads.txt across Oath’s properties,” an Oath spokeswoman told Business Insider. “Working closely with publishers and approved resellers, we will begin enforcing ads.txt across our platforms and filtering inventory on domains where our DSPs buy.”

Ad fraud has been a pervasive issue in the digital advertising industry for years, and there are multiple ways with which fraudsters make it happen. Hackers often sell ads on fake websites using computer programs called “bots” that mimic human behavior — and make it look as though real people are visiting websites or clicking on ads. There’s also the aforementioned spoofing, where entities claim to have the rights to sell publishers’ ads when they don’t.

A large industry-wide push for better transparency in digital-ad buying has taken shape this year, following a string of recent instances of ads ending up in dicey corners of the internet. And ads.txt has perhaps been at the forefront of that, with big marketers like Procter & Gamble, players like Google and big ad firms like Digtas putting their weight behind it.

While ads.txt will ultimately help raise publisher ad inventory that has been devalued by counterfeit inventory in the market, some publishers have still been hesitant to take the leap, said Marc Goldberg, CEO at Trust Metrics, a company that monitors digital transparency, quality and fraud.

“There’s still confusion, but publishers need to do this because of the risks they face, and are still losing money,” he said.

To see the full story – click here