In every field, every industry, and in almost every way, the world keeps moving more towards automated processes.

For publishers filling online ad space, the introduction of automation has presented an efficiency previously not available. It better optimizes ad space, with more stable placements, less wasted inventory, and higher guaranteed return on that inventory.

Hands-On Ad Buying

Prior to automation, publishers would see a great deal of their ad inventory go to waste. In essence, it took more time for them to fill less ad space.

Before the introduction of automation, ad buying was a human-based process.

For any single ad placement, a buyer and salesperson had to come together, discuss, negotiate, and agree on a deal. This included manually filled-out RFPs and insertion orders.

Manual paperwork and human negotiations, as you could imagine, took up a lot of time for both ad buyers and sellers.

In Comes Programmatic

Programmatic ad buying is the process of automated ad buying, where it is not human beings in contact with one another, but software.

Now, human interaction with ad buying happens almost entirely before the process begins. Human ad buyers and sellers essentially lay the infrastructure for the process, and automation does the rest.

The waters get a bit murky when considering the process of programmatic ad buying, however. While most understand its benefits, not everyone truly understands how the process actually works.

So then, how does the process work?

As you’ll see (in a forthcoming post), there have been advancements just within the programmatic process itself. To understand those advancements, however, it’s important to know how the traditional process plays out.

The original programmatic ad buying process is known as “waterfalling.”

First, think of a waterfall…

It flows downward, in a single, set path. Now, think of a series of rocks, standing in a vertical line. Think about how the water would meet each of those rocks individually, if they were set beneath a waterfall.

The water would reach the rocks in order. It would hit the first, and then only hit the second rock having already hit the first, and so on. The water meets each rock in sequence.

That is a broad representation of programmatic waterfalling, and is where the name comes from.

That merely scratches the surface, however. Let’s dive a little deeper…

It’s not the simplest process, so we’ve broken it down in a much more digestible way:

How It Works

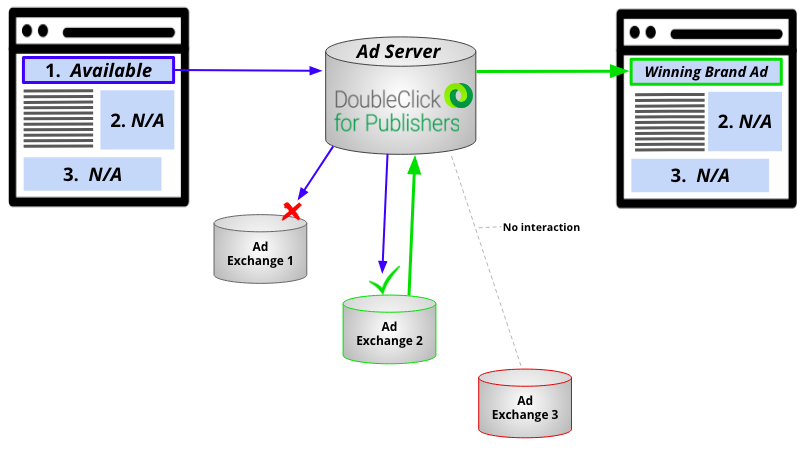

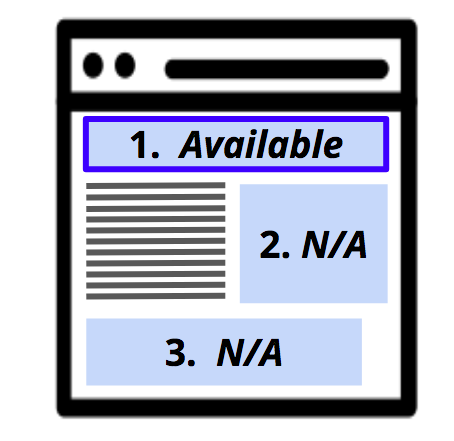

The programmatic process begins by determining what ad placements on a given webpage are available to buyers. Simply put, “what location on the page is for sale?”

Once those places are determined, the seller needs to set a price floor for the available placement.

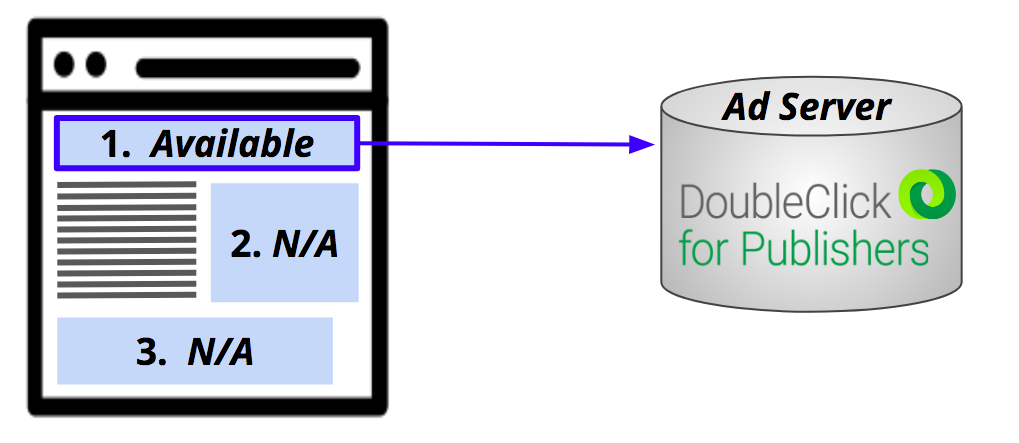

Once that price floor is set, the ad server is introduced.

An ad server is essentially an enforcer for the price floor. It’s the ad server’s job to communicate with ad exchanges.

An ad exchange is a marketplace where individual auctions are held for brands to bid on available ad inventory.

In the waterfalling process, the ad server reaches out to ad exchanges sequentially, one at a time, and those ad exchanges present their highest received brand bid to the server.

If the bid does not meet the price floor, then the server will move onto the next ad exchange. This process is repeated until an exchange presents a bid that meets or exceeds the price floor.

The first bid that meets the price floor is accepted, and the brand that made the bid wins the placement – their ad will appear on the webpage.

Confused? Don’t worry. We know it’s a bit much to handle.

Let’s look a little more closely at the graph above…

Consider the following example:

What’s for sale?

It’s been determined that Placement 1 is available to buyers. Placements 2 and 3 are being sold directly to buyers, therefore, are not available.

The seller now sets the price floor for Placement 1. Let’s say the seller sets the price floor at $3.00.

This is where the ad server comes into play and automation officially begins. In this example, the ad server is DoubleClick for Publishers.

Now that the price floor is set, DoubleClick will reach out to its primary ad exchange, in this example, Ad Exchange 1.

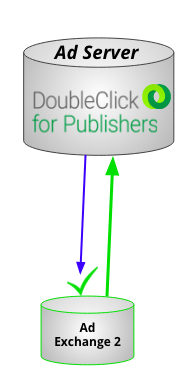

Ad Exchange 1 presents its highest bid of $2.50 to DoubleClick. This does not meet the price floor of $3.00, so DoubleClick then moves on to Ad Exchange 2.

Ad Exchange 2 presents a bid of $3.20, which meets the price floor, therefore ending the bidding process. The brand that made the $3.20 bid wins the placement, and their ad will appear on the webpage.

This is where it’s most important to consider the “waterfalling” method of communication, however.

Since DoubleClick is reaching out to ad exchanges sequentially, it never even communicates with the next ad exchange.

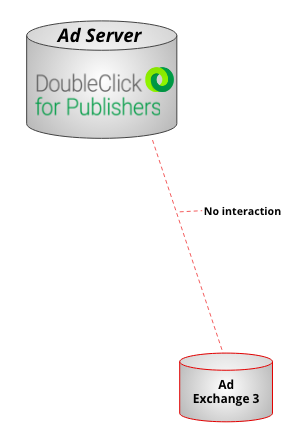

The problem here, is that Ad Exchange 3 was essentially left waiting in line with a $4.00 bid, which would have been the highest bid received overall.

While this process much improves on previous ways of placing ads, it creates a situation where the highest bid may not even be considered. Waterfalling does not consider all bids.

With waterfalling, publishers are not maximizing the value of their inventory. While they can efficiently fill their ad space, they may also be squandering opportunities for more money.

Where opportunity is lost, however, is a possibility for growth, as evident by the introduction of header bidding.

But, what the heck is header bidding?

In our next post, we’ll breakdown header bidding, how it works, and why it is the newest advancement in programmatic advertising.