Google’s always been strict on privacy.

In 2017, Google announced that Chrome would instill stricter ad-blocking standards. The announcement raised speculation, as publishers and advertisers were left to wonder exactly which ads would be blocked and how Google would handle violators.

In December of that year, Google gave “an update on Better Ads,” officially confirming that “Starting on February 15, in line with the Coalition’s guidelines, Chrome will remove all ads from sites that have a ‘failing’ status in the Ad Experience Report for more than 30 days.”

Now that these standards are officially in place, however, it’s important that publishers and advertisers know exactly what is being blocked, given that Chrome currently holds more than 64% of the global web browser market share.

And, more importantly, what does Google’s advertising future look like?

What is the Coalition for Better Ads®?

The Coalition for Better Ads is an alliance of companies and associations that have come together in an effort to give internet users the best possible experience with advertising. The Coalition put the Better Ad Standards in place to clarify how content producers can best interact with viewers and serve ads in a way that is not annoying or intrusive.

The Coalition for Better Ads developed the Better Ad Standards based on “comprehensive research involving more than 25,000 consumers” while citing “Extensive consumer input and empirical data” as factors in shaping the new standards.

In a broad sense, the Better Ads Standards were implemented to create a more user-friendly online experience, ridding of the most annoying, least preferred ads on both desktop and mobile.

But what do we, as internet users, prefer the least?

What Exactly Is Google Chrome Blocking?

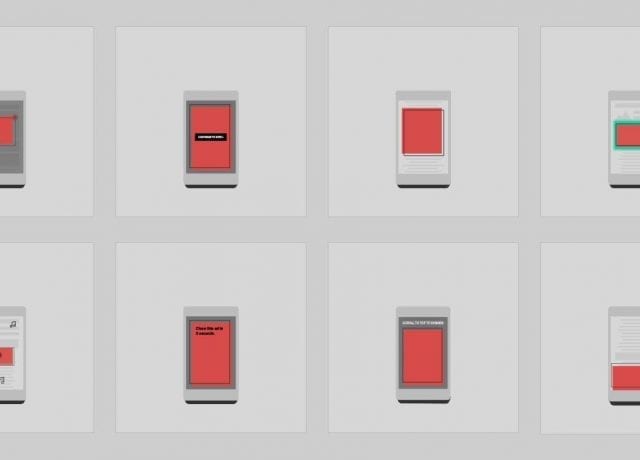

Google Chrome is blocking 12 types of ads across desktop and mobile (four types of desktop ads and eight types of mobile ads).

Desktop Ads

This one should not come as a surprise to many.

Pop-up ads have long existed to the disdain of internet users. When considering ads as “disruptive,” nothing is quite as disruptive as an ad that pops up in front of the content a web user is trying to enjoy.

The Coalition’s website states that pop-ups “are among the most commonly cited annoyances for visitors to a website.”

People are generally not fond of anything that disrupts their experience to this level—82.2% of the sample from G2’s study said they hated email pop-ups.

Auto-playing Video Ads with Sound

We’ve all had it happen… You’re scrolling through a tremendous article when suddenly, noise erupts from somewhere unknown.

Before you realize that there’s an auto-play video ad on the page, you’re jolted from concentration and left searching for the “mute” or “close [X]” buttons.

Video ads that require a click to activate sound did not fall beneath the Better Ads Standard and are, therefore, still allowed.

Auto-play ads are a hot topic outside of Chrome’s walls.

Traditionally advertisers have opted for it due to the ability of auto-play ads to introduce words rather than just text and subtitles. While Facebook and other popular advertising ecosystems allow advertisers to launch auto-play ads, they make it just as easy for users to disable them, which many of them do.

Prestitial countdown ads are the ads that appear before a page’s content loads, forcing the reader to wait a few seconds before allowing them to click and continue.

The Coalition states that these ads “can disrupt users in a way that dissuades them from waiting for the countdown to finish and continuing onto their content.”

They also note that for desktop, prestitial ads without a countdown do not fall below the Better Ad Standards’ threshold for acceptability and are thus okay for publishers to use.

This begs the question: What about pre-roll ads on YouTube and popular OTT streaming services? Ads that play before content—and “count down”—are widely popular in these ecosystems and generally excepted by users.

Large sticky ads attach themselves to the bottom of a page of content, staying there as the user scrolls down the page. To qualify as “large,” a sticky ad must take up more than 30% of a desktop screen’s real estate.

Regardless of the device, consuming content on a full-screen is always much more preferred by viewers, especially on mobile devices that people generally hold vertically. That’s good news for advertisers as it allows them to maximize real estate on mobile devices.

Mobile Ads

For pop-up ads, there’s not much difference between desktop and mobile. According to internet users, they’re annoying no matter where they appear.

For desktop and mobile, pop-ups with and without countdowns fall beneath the threshold for viewer acceptability.

Prestitial mobile ads, like on desktops, appear before the content of a web page loads. The difference on mobile, however, is that all prestitial ads are restricted, not just the ones with a countdown.

On mobile, prestitial ads tend to take up more real estate, which, even without a countdown, can make them more disruptive than on desktop.

“Ad density is determined by summing the heights of all ads within the main content portion of a mobile page, then dividing by total height of the main content portion of the page.”

In short, within a piece of content, a publisher may not have more than 30% of the space in which that content sits being filled by advertising.

When considering the “content portion” of the page, that only means the real estate where the content sits, excluding headers, footers, and anything outside the content itself. The 30% also applies to the entire content portion of the page, the page in total, not just what is viewable on a user’s screen.

Sticky ads count toward ad density, with the height being counted toward the page’s ad density percentage. Video ads “that appear before or during video content that is relevant to the content of the page itself are not included in the measurement.”

The Better Ad Standards restrict the use of “ads that animate and ‘flash’ with rapidly changing background, text or colors” because they can be “highly aggravating for consumers, and serve to create a severe distraction for them as they attempt to read the content on a given page.”

Not all animated ads are blocked on Chrome – only the ones that rapidly flash.

Auto-playing Video Ads with Sound

As they are on desktop, auto-play video ads on mobile are also restricted.

Users won’t have to worry about finding the “mute” button on Chrome for mobile anytime soon.

Postitial countdown ads appear after a user has followed a link in a piece of content.

Once they follow a link, the ad appears with a countdown, making the user wait before they can be redirected to the page they were trying to access.

Much like prestitial ads with a countdown, users may be inclined to leave the page once they see a postitial countdown appear, as it makes them wait to enter the following page.

Scrollover ads are unlike inline ads, as they do not move with the content on a page but instead sit on top of it.

Scrollover ads, in a certain sense, can almost be looked at as something similar to a pop-up since they lay on top of content, obstructing it from view.

The Coalition for Better Ads refers to these ads as “disorienting” for mobile users, as they may distract users from the content they’re trying to read.

On mobile web browsers, large sticky ads can appear on more than just the bottom of the page but serve the same static disruption that sticky ads do on desktop browsers.

* All images and quotations used above are from https://www.betterads.org/standards/. Visit the site to see the full breakdown of the Better Ads Standards.

What happens to violators?

Sites that violate Google Chrome’s ad blocker and use at least one of these ad types will first be notified by Google that they are violating the Better Ad Standards and given 30 days to remedy the issue.

If the site owner repeatedly violates the new standards and ignores Google’s notifications for those 30 days, only then will Chrome start blocking all of the ads on that site.

So, while Google is putting in great efforts to make online advertising better for everyone, the metaphorical gavel is not being dropped on violators as quickly as many had initially anticipated.

Still, the risk of a publisher losing all their online advertising is likely not something they want to play around with.

There is no question that these changes are, at the least, the beginning of a much better user experience with advertising on the internet.

This brings us to our next topic: What else is Google doing to tackle the user experience.

Google Sunsets Third-Party Cookies

Stricker ad-blocking standards aren’t the only measure Google is taking to ensure the millions of people who use its browser don’t get tired of ads.

Google is also sunsetting third-party cookies in 2024 (after delaying it for several years). The delay not only gives Google more time to test its Privacy Sandbox but gives advertisers more time to prepare for a world without their beloved third-party cookies.

The impending deprecation is understandably concerning for advertisers, considering more than 80% of senior marketers in the U.S. rely on third-party cookies.

Third-party cookie alternatives

So, what will advertisers use when Google says goodbye to third-party cookies next year?

If they want to advertise on Chrome, Google’s Privacy Sandbox will likely be the solution. But other alternatives exist, including The Trade Desk’s Unified ID 2.0, which allows for targeted advertising without revealing the end user’s true identity. Other likely third-party-cookie alternatives are email addresses and phone numbers.

Outside of Google’s walls, retail media will continue to gain steam as consumer brands capitalize on first-party shopper data.

For more insights, sign up for MediaRadar’s blog here.